By Lisa Labita Woodson

Globally, women experience a disproportionate burden of disease and death due to inequities in access to basic health care, nutrition, and education. In the face of this disparity, it is striking that leadership in the field of global health is highly skewed towards men and that global health organizations neglect the issue of gender equality in their own leadership.

— Downs, Reif, Hokoror & Fitzgerald, 2014

This is an excerpt from Increasing Women in Leadership in Global Health published in the Academic Medicine Journal, highlights a key issue in global health that resonates deeply with me: even though there is substantial emphasis on women’s health and reducing gender disparities, many of the decisions that impact programs and policies within organizations are predominantly led by men. This observation underscores the gap between the rhetoric focused on gender equity and the reality of decision-making in the field of global health.

I was encouraged to write this editorial because we, the editors at BGH, are not only global health researchers, but women of color with distinct backgrounds and experiences, and mothers. We have all had our own struggles working in this field of which 70% of leadership roles are held by men but the work is predominantly carried out by women. We are also further penalized in the workforce once we become mothers. How do we move beyond this?

Downs, Reif, Hokoror & Fitzgerald (2014) showcases studies that provide intriguing evidence of how female leadership impacts communities. In a study conducted in India, it was found that the number of elected women is directly proportional to the decrease in neonatal deaths (newborn, up to one month of age). Women were also more likely to invest in public works that were more closely aligned with women's concerns, for example, clean drinking water; whereas men were largely focused on works linked to men's concerns like farming. Women leaders are also more likely to favor health infrastructure, and programs focused on antenatal care and immunizations.

But how does that relate to women in the global health workforce? In my opinion, the authors were pointing to how female leadership drives different priorities not only at the community level, but also within our own field by expanding the health agenda. The paper then highlights that although there are a greater number of women at the undergraduate and graduate levels interested in global health and within the workforce, fewer than 25% of leadership roles are held by women in the field. The authors hypothesize that women leave the global health career path because of 'gender-based obstacles' they encounter. These obstacles include challenges climbing the institutional career ladder, tensions between career and family responsibility, and health/safety concerns.

Potential solutions are also offered to help overcome these barriers, like providing greater mentoring opportunities, more global health research enabling grants, and extended maternity leave.

Through some online searching, I came across the non-profit organization, Women in Global Health. It was established in 2015 and works "to encourage stakeholders from governments, civil society, foundations, academia and professional associations and the private sector to achieve gender equality in global health leadership in their space of influence." This discovery led me to a research paper published by Women in Global Health and the World Health Organization (WHO). The paper titled, Delivered by Women, Led by Men, examines gender and equity in the global health workforce. They identified and reviewed over 170 studies, and although the research is largely lacking in low and middle-income countries, they were able to identify critical trends that would first need to be addressed in order to put forth policy recommendations. Some of their key findings show that:

Overall, they recommend greater recognition of the gender disparity in the global health workforce and the adoption of gender-transformative policies that address the causes of gender inequities. This would help to "maximize women's economic participation and foster empowerment through institutionalizing their leadership, addressing gender biases and inequities in education and the health labor market, and tackling gender concerns in health reform processes." But these policies would need to be contextualized across countries and be reinforced across government and private sectors.

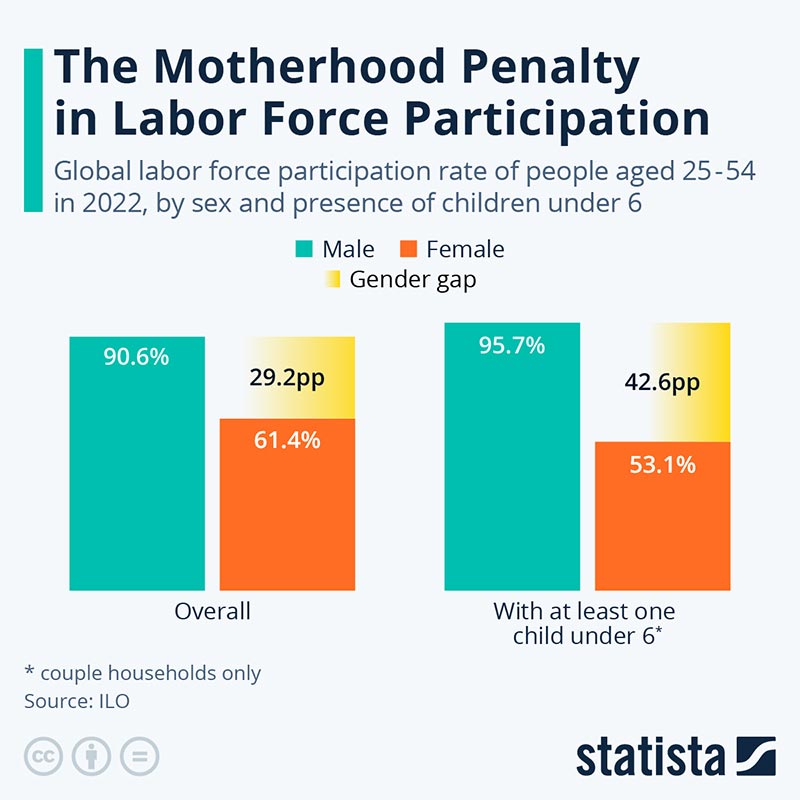

Recently, the groundbreaking research of Dr. Claudia Goldin on women in the workforce has been recognized with a Nobel Prize in Economics. She sheds light on what's commonly known as the "motherhood penalty” in the context of gender disparities in career trajectories. Her research reveals that women, particularly after the birth of their first child, experience a reduction in earnings and working hours, and struggle to compensate for this loss as their children grow older. Remarkably, fathers do not encounter the same career setbacks. While her research focused on the careers of MBAs, its implications are pertinent to examining gender disparities in other fields like global health.

Within many families and cultures, women continue to bear a disproportionate share of caregiving responsibilities. Furthermore, they confront discrimination and bias in hiring, promotions, and compensation. Balancing caregiving with professional obligations is already a formidable challenge, and these additional obstacles exacerbate the struggle. This underscores the importance of implementing flexible work arrangements and policies such as paid parental leave to facilitate mothers' continued participation in or return to the workforce after giving birth.Here is a graph by Statista that helps illustrate the “Motherhood penalty” in the global labor force:

I am no stranger to sexual discrimination and harassment having worked in this field for over a decade. I also know that I have been paid less than my male colleagues for doing the same work. I have not always had the opportunity to represent my own work; often passed off to a male counterpart or supervisor, especially in the presence of funders or clients.

But in the moment of #MeToo, I feel that there is more awareness of these gender issues, and organizations such as Women in Global Health have created a space for women activists to demand for greater gender equality in this field.

Now, we are a collective force, we have the power to push beyond these barriers, together, for better pay, respect, and upward mobility. Because we are women of global health.

©2024. Made with (❤︎) in Yachayninchik